October 2020, Canada: on my short trip to the southwesternmost tip of Canada at the time, I encountered various animal species that I had never seen in the wild before. From sea lions to bears, from bald eagles to ... there were some unknown and new things.

One of these unknown birds was the Belted Kingfisher. It belongs to the group of kingfishers (Alcedinidae) and is the only relative of our native kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) that occurs in Canada.

As my interest in photography grew, so did my interest in nature. After all, you want to know what's in front of your lens. I am not an ornithologist and only read up on the individual species that I have been given as a photo motif. Depending on how much time you have, it takes a while to get an almost complete portrait of a species, in this case the kingfisher.

The first encounter with a kingfisher in Canada was not to be the last. Back in Germany, I began to go on photo tours more often and use my camera more intensively. In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, I then encountered the native representative of kingfishers quite regularly. I encountered them in wooded areas with ponds as well as along rivers and lakes. I noticed many details that I would like to report on.

Belted Kingfishermen in Canada

I spotted the Canadian representative of the kingfishers in 2018 in Canada on Vancouver Island at Fanny Bay. To be precise, it was a belted kingfisher. I was using the Nikon D7500 with the 55-300mm lens (for APS-C) from Nikon at the time. I had no idea about the right settings or which lenses you need for such shots. At least it was enough for a few snapshots back then.

I had spotted the small white-blue/grey-striped bird on a stone on the bank. When I tried to get a little closer to it, it sped off and sat on another stone parallel to the bank. So I cautiously followed it, of course with the photographer's goal in mind of reducing the distance between me and the animal for better pictures. Mind you, I had no camouflage. I was basically just walking along the stony beach with my camera. As soon as I got closer to the rocket bird (30m), it flew up and landed back on the rock it had been sitting on. We played this game a few times. And somehow I had the feeling that he was just trying to annoy me. But of course I know that he saw me as a potential threat or at least a nuisance. So I quickly left him alone again. I still managed to get a few shots.

The native kingfisher (Alcedo atthis)

The native kingfisher is found in Europe, Asia and North Africa. It is found in calm flowing waters.

The two sexes of kingfishers are easy to distinguish. A nice distinguishing feature between males and females is the orange-colored lower beak of the female. The male tends to have a black beak, the base of which may have a light-colored spot.

My first attempts to capture the local kingfisher with my camera were with the D500 camera and the Sigma 150-600mm C lens. The pictures were not necessarily of high quality or satisfactory. This technical combination proved to be quite challenging. The images were low-contrast, not super sharp and taken from a great distance. As a result, the kingfisher was not particularly well resolved. For cleaner photos, I therefore took the Nikon D750.

When you start to observe the individual animals with the camera, you learn a lot about their behavior.

Behavior of the animals

So far, I have mainly been able to observe the little blue-orange birds during courtship or while fishing.

There seem to be two strategies for fishing:

1. fishing from a perch: the kingfisher sits on reeds, sticks or branches that often protrude above the water and stares into the water. The bird waits for the right moment to swoop down as fast as an arrow and, in the best case, successfully emerge with its prey.

2. shaking flight over the water: During my first attempts at photography in particular, there were those typical "I wish I had stayed longer" moments. I had just packed up my camera after several hours of waiting when one of the two kingfishers of a couple came swooping around the corner, stood like a hummingbird or kestrel in the air above the water for a few seconds, perhaps 3 m away from me, swooped down into the water, came back out with fish and flew away.

From a physical point of view, it makes sense to use the second hunting strategy only occasionally. With sufficient visibility and prey, the flight time can be kept short, as the shaking is incredibly energy-consuming.

However, interesting correlations emerged in both situations, which could be observed particularly well with two kingfishers in Rostock. In a west-facing canal, the water is heavily shaded by trees in the morning. Only when the sun has moved far enough or has reached a certain altitude do the kingfishers come into the canal to fish. Apart from the necessary water quality, brightness also plays an important role here!

In the wooded area that I visited regularly, there were also two other conspicuous features that the kingfishers displayed there. There seemed to be an entry route and an exit route. In other words, more or less typical paths that the bird systematically uses to get to and from its nesting site. Movement sequences that occur regularly, repeatedly and consistently in kingfishers (stereotypical behavior). This can be of great benefit to a photographer like me. After all, it also provides a better opportunity to photograph the little blue dart head-on in flight. I haven't managed it yet, but let's see 🙂

Kingfishers very often announce their arrival with a high Fiep sound before they fly in (forwarding to https://www.deutsche-vogelstimmen.de). In my opinion, this is a very typical call that can be easily distinguished from other forest or water birds due to its high frequency and hoarse conciseness. You can hear their call regularly, especially during the mating season, when they make their mating flights in February/March. It has to be said, however, that not so long ago I had contact with a couple who didn't make a single sound for over 1.5 hours. That was in the MONTH during the breeding season. They tend to be quiet and concentrate solely on foraging. So you should never rely on getting a regular signal from the bird. Then it just sits quietly on its perch, looks for prey and disappears to the next spot without making a sound. So it also depends on the time of year.

Winter 2021

The winter of 2020/2021 was a special one compared to previous years. At the beginning of February, temperatures around Rostock dropped to minus 15 degrees in some places. The Warnow and its small tributaries were completely frozen over. The word "ice" in kingfisher does not mean that the kingfisher prefers cold regions. The kingfisher hunts in open waters and catches small fish. Due to its high metabolism, it eats half of its own body weight per day. It therefore needs a regular supply of food, especially in winter. After all, it has to keep itself warm in permanently sub-zero temperatures. This consumes more energy. Waters also freeze over, making access to food sources more difficult. A long, cold winter in which the waters freeze over can even mean the death of an entire kingfisher population.

Sometimes the kingfisher then has to move on. This is not only a high energy cost, it also carries the risk of finding no or worse alternative sites. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/nach-elf-tagen-schnee-und-eis-die-haelfte-der-berliner-eisvoegel-ist-verhungert/26923728.html

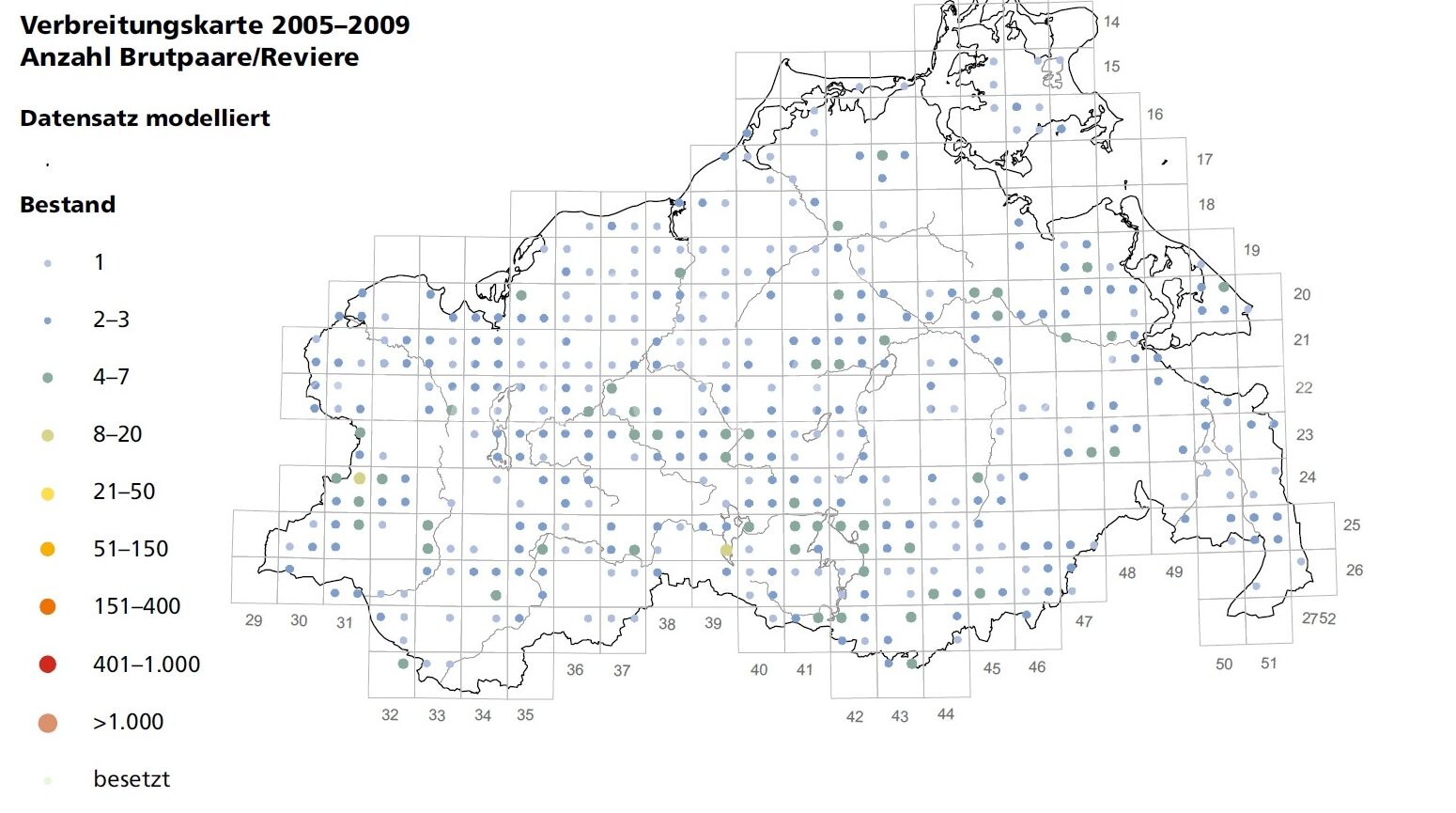

On the side of the OAMV (forwarded by Interessengemeinschaft Avifauna Mecklenburg Vorpommern), there are significantly fewer sightings of the kingfisher in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern with the start of the cold period in 2021, right into early summer. Based on the current population situation (see distribution map on the left), there is still very little risk of a threat. The bird's reproduction rates are generally quite high (Vökler, F. (2014): Second atlas of the breeding birds of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Greifswald). A survival strategy to compensate for harsh winters in the following years. Therefore, it can at least still be assumed that short, harsh winters such as 2021 can be compensated for quite quickly.

If you would like to read up on this and study the distribution areas in more detail, you can visit the website of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species with the kingfisher in more detail.

Hazard

The overall population of kingfishers appears to be relatively stable, at least according to my knowledge (https://www.wildtierschutz-deutschland.de/single-post/eisvogel). However, there are indications that this is no longer the case everywhere. A particularly striking local example is Lake Plau in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Increasing tourism and the use of water by motorized boats are depriving animals such as the kingfisher of their retreats, breeding grounds and hunting grounds. What used to be a natural paradise is being polluted with noise, exhaust fumes and garbage, with no consideration for the species that live there. Local residents report that sightings of kingfishers have become rarer and fewer in recent years. Taking this development into account, Lake Plau will probably not be the only ecosystem to be destabilized by human use.

The main threats are bank obstruction and settlement along watercourses, water pollution and heavy recreational use. Illegal shooting and trapping along bodies of water certainly play a role, but the unintentional or deliberate destruction of actual and potential nesting sites is probably more serious. (https://www.lfu.bayern.de/natur/sap/arteninformationen/steckbrief/zeige?stbname=Alcedo+atthis)